Reducing a product’s environmental impact by 80% isn’t about following a green checklist; it’s about mastering the strategic trade-offs at the concept stage.

- Effective eco-design requires arbitrating between conflicting goals like durability versus recyclability and material purity versus performance.

- Design decisions on assembly, materials, and packaging have cascading effects on repairability, recycling contamination, and carbon footprint.

Recommendation: Prioritize design choices that anticipate and eliminate downstream problems, from enabling simple repairs to ensuring clean material recovery at end-of-life.

As industrial designers and engineers, we are trained to solve problems. We sculpt form, optimize function, and build value. Yet, the most significant problem we face today is one of our own making: the environmental impact of the products we create. The common discourse offers simple solutions: use recycled materials, reduce packaging, make things recyclable. While well-intentioned, these are merely starting points, not the full equation.

The true challenge of eco-design lies not in following rules, but in navigating the complex, often conflicting, decisions that arise during the creative process. The concept phase is where the battle for sustainability is won or lost. In fact, research from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation demonstrates that up to 80% of environmental impacts are determined at the design stage. This is our moment of maximum leverage, where a choice between glue and a screw, or one polymer over another, can dictate the fate of a product decades from now.

This guide moves beyond the platitudes. It focuses on the critical trade-offs and decision points that define modern eco-design. We will not offer a simple checklist, but rather a framework for thinking critically about the real-world compromises between repairability and aesthetics, durability and recyclability, or innovation and infrastructure. It is in mastering this art of the strategic trade-off that we can unlock genuine, substantial reductions in a product’s lifecycle impact.

This article explores the key decision points you will face in the design process. By understanding these challenges and the strategies to navigate them, you can transform your design philosophy from simply creating products to architecting sustainable systems.

Summary: Mastering Eco-Design for Maximum Impact

- Why Using Glues Instead of Screws Kills Repairability?

- How to Choose Monomaterials to Ensure 100% Recyclability?

- Built-to-Last vs Built-to-Recycle: Which Strategy Lowers Lifecycle Carbon More?

- The Over-Packaging Mistake That Negates Your Eco-Friendly Product Design

- When to Update a Product Design to Incorporate New Bio-Materials?

- The Recycling Error That Turns Macro-Plastics into Micro-Plastics

- The Design Mistake That Alienates Customers and Invites Regulation

- Virgin vs Secondary Materials: How to Overcome Quality Inconsistencies in Production?

Why Using Glues Instead of Screws Kills Repairability?

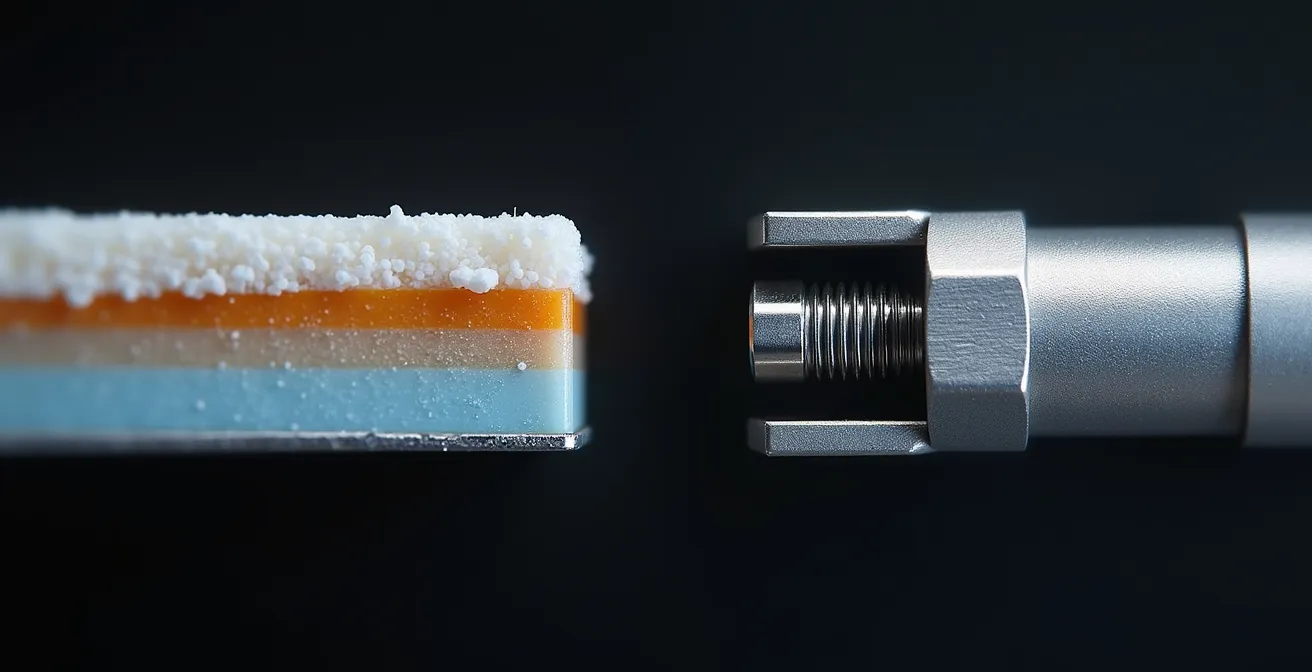

The choice between adhesives and mechanical fasteners is a classic design trade-off. Glue offers a seamless, often cheaper, and lightweight assembly, creating a clean, monolithic form. Screws, on the other hand, speak a language of assembly, maintenance, and disassembly. This decision point directly pits manufacturing efficiency and minimalist aesthetics against a product’s potential for a second life. A glued product is often a sealed product, where accessing a single failed component means destroying the entire chassis. This creates a “repairability deficit” where the cost and effort of disassembly far outweigh the value of the harvested parts.

This isn’t just about making repairs possible; it’s about making them practical. Designing for disassembly means thinking like a repair technician. Are standard tools sufficient? Can high-value components be accessed without damaging lower-value ones? By defaulting to adhesives for their perceived simplicity, we are often designing for disposal. The sleek object becomes, in effect, a beautiful piece of future landfill.

As the image above illustrates, the difference is fundamental. One method creates a permanent, often irreversible bond, while the other creates a firm but reversible connection. To move forward, we must reframe the challenge: how can we achieve the aesthetic and structural integrity of bonding while preserving the serviceability of mechanical fastening? This might involve designing elegant modular interfaces, using snap-fits, or creating visible, celebrated fastening points that become part of the product’s design language. The goal is to make the right choice, not just the easy one.

How to Choose Monomaterials to Ensure 100% Recyclability?

The pursuit of 100% recyclability often leads designers to a simple, elegant solution: the monomaterial. A product made from a single, pure material (like PET, aluminum, or polypropylene) sidesteps the complex and often impossible task of separating co-molded plastics, laminates, and composites at its end-of-life. When a recycler receives a clean stream of a single material, the process is efficient, and the resulting secondary material retains high quality. This is the circular economy in its purest form.

However, the trade-off is significant. We rely on composites and multi-material constructions for a reason: they deliver superior performance. A soft-touch TPE overmold on a rigid ABS handle provides grip. A metallic film on a polymer substrate offers a premium finish. Abandoning these for material purity can compromise durability, aesthetics, and user experience. The strategic question for the designer is not “Should I use a monomaterial?” but “Where can I use a monomaterial without fatally compromising the product’s function and appeal?”

The table below outlines the strategic trade-offs between different material approaches. It highlights that while pure monomaterials offer the highest recycling rates, smart composites that use mechanical interlocks instead of adhesives can achieve excellent performance with only a minor hit to recyclability. The key is designing for separation.

| Design Approach | Recycling Rate | Performance | Cost Impact | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Monomaterial | 95-100% | May compromise aesthetics/durability | +15-30% material cost | Short lifecycle products |

| Smart Composite (mechanical interlock) | 85-95% | Optimized performance | +5-10% assembly cost | Durable goods |

| Surface-treated Monomaterial | 60-80% | Premium aesthetics | +10-20% processing | Consumer electronics |

Ultimately, designing with monomaterials is an exercise in creative constraint. It forces us to find new ways to achieve texture, color, and structure through form and process—such as molded-in patterns instead of paint, or clever structural ribs instead of a reinforcing layer. It’s about achieving richness through purity.

Built-to-Last vs Built-to-Recycle: Which Strategy Lowers Lifecycle Carbon More?

One of the central strategic dilemmas in eco-design is the tension between durability and recyclability. The “Built-to-Last” philosophy favors robust materials, over-engineered structures, and timeless design to extend a product’s usable life as long as possible, avoiding the need for replacement. The “Built-to-Recycle” approach accepts shorter lifecycles, especially for products with high rates of technological obsolescence, and prioritizes easy disassembly and pure material streams for efficient recycling. Neither is universally superior; the optimal strategy is entirely context-dependent.

For a product with low technological obsolescence and minimal energy use during its life (like a piece of furniture or a hand tool), the “Built-to-Last” strategy is almost always the winner, drastically reducing the carbon impact of manufacturing replacements. However, for energy-intensive products in rapidly evolving sectors (like home appliances or smartphones), the equation changes. A highly durable but inefficient 15-year-old refrigerator can have a far greater lifetime carbon footprint than three shorter-lived, but progressively more efficient, models. Indeed, lifecycle analysis research reveals that products designed to last 10+ years can result in 40% higher lifetime emissions if energy efficiency improvements of 5% annually are foregone. This is the “rebound effect” in action.

The most elegant solution often lies in a hybrid approach: modular design. This involves creating a durable, long-lasting chassis or frame while designing key functional or technological components as easily replaceable modules. This strategy allows a product to adapt and evolve, accommodating efficiency upgrades or new features without requiring a full replacement. It’s the best of both worlds: a core built to last, with elements designed for change.

| Product Category | Tech Obsolescence Rate | Use-Phase Energy | Optimal Strategy | Carbon Reduction Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furniture/Tools | Low (10+ years) | Zero/Minimal | Built-to-Last | 60-80% reduction |

| Smartphones/Laptops | High (2-4 years) | Moderate | Modular + Recyclable | 40-50% reduction |

| Home Appliances | Medium (5-10 years) | High | Efficiency upgrades + Recycling | 50-70% reduction |

The Over-Packaging Mistake That Negates Your Eco-Friendly Product Design

Packaging is the first physical interaction a customer has with a product, and its design is a delicate balance between protection, brand experience, and environmental responsibility. Too often, a thoughtfully eco-designed product is let down by its packaging. The mistake isn’t just about using non-recyclable materials; it’s the hidden impact of “shipping air.” Inefficient packaging that is oversized or requires excessive void-fill materials drastically reduces shipping density, meaning fewer products fit into a container or truck. The result is more vehicles on the road, burning more fuel to transport the same amount of goods.

The unboxing experience is another critical trade-off. A premium feel is often associated with multiple layers, complex inserts, and luxury materials. However, a memorable experience can be created with far less. The challenge is to shift the perception of luxury from material excess to design intelligence. This can be achieved through clever structural design, high-quality monomaterials, and a focus on tactile qualities like embossed patterns instead of ink-heavy printing.

Case Study: Volumetric Efficiency and the Hidden Carbon Cost

An analysis of packaging volumetric efficiency reveals that poorly designed packages can increase transport emissions by up to 60% by reducing container load density. Companies implementing “design for logistics” approaches, where product form factors are optimized for shipping density, have achieved a 30-40% reduction in transport emissions. They often eliminate the need for protective packaging entirely through the strategic use of reusable totes and designing products with interlocking geometries that self-protect during transit.

An innovative approach is to design “second life” packaging that transforms into something useful, like a storage box, a smartphone stand, or a children’s toy. This not only eliminates waste but also extends the brand’s positive interaction with the customer. The most sustainable packaging is often the one that isn’t thrown away. The ultimate goal is to design the product and its package as a single, integrated system, where the product’s own geometry provides protection and the packaging is minimal, smart, and valuable.

When to Update a Product Design to Incorporate New Bio-Materials?

Bio-materials, such as PLA, PHA, or mycelium-based composites, promise a future of compostable products and a reduced reliance on fossil fuels. For a designer, they represent an exciting new palette of textures, forms, and sustainable narratives. However, incorporating them is not a simple swap. It’s a strategic decision that requires a thorough assessment of the material’s maturity, the available infrastructure, and potential unintended consequences.

The primary trade-off is between innovation and reality. A product made from industrial-compostable PLA is only sustainable if the end-user has access to industrial composting facilities. If not, the product is likely to end up in a landfill, where it may not biodegrade as intended, or worse, in a recycling bin. This is where the most significant danger lies: contamination. Many bio-plastics, particularly PLA, are visually indistinguishable from PET. Even a small amount of cross-contamination can ruin entire batches of recycled material. For example, according to recycling industry analysis, just 2% contamination of PET recycling streams with look-alike PLA can render a batch unusable, leading to it being downcycled or landfilled.

Before committing to a new bio-material, a rigorous readiness assessment is crucial. This involves not just technical performance testing but a full system analysis, from supply chain stability to consumer education. The decision to switch must be based on data, not just on the marketing appeal of being “bio-based.” A premature switch can do more harm than good, undermining consumer trust and damaging recycling systems.

Action Plan: Bio-Material Readiness Assessment Framework

- Evaluate complete lifecycle impact: Assess factors beyond end-of-life, including land use, water consumption, and agricultural inputs for the feedstock.

- Verify infrastructure availability: Map the existence and accessibility of industrial composting facilities in all target markets for the product.

- Test for recycling contamination risk: Conduct tests to understand how the material behaves if it mistakenly enters existing PET or HDPE recycling streams.

- Assess supply chain stability: Investigate the reliability of material suppliers, historical price volatility, and dependence on single-source feedstocks.

- Calculate total switching costs: Account for not just material price, but also retooling for new manufacturing processes, obtaining new certifications, and funding consumer education campaigns.

The Recycling Error That Turns Macro-Plastics into Micro-Plastics

We design for recyclability, but we rarely consider the violence of the recycling process itself. Mechanical recycling involves shredding, washing, and melting. During the shredding phase, the material properties of the plastic dictate how it breaks apart. This is a critical, and often overlooked, source of microplastic generation. A design that appears perfectly recyclable on paper can, in reality, be a machine for turning large plastic objects into trillions of tiny, environmentally persistent particles.

The key factor is the material’s ductility. Ductile polymers like HDPE and LDPE tend to tear and stretch when shredded, creating larger, more manageable flakes. Brittle plastics, such as polystyrene (PS) or certain grades of polypropylene (PP), are far more problematic. They shatter on impact, creating a fine dust of microplastic particles that can easily escape filtration systems and contaminate the water used in the washing process. This turns recycling facilities into unintentional point sources of microplastic pollution.

Case Study: Material Brittleness and Microplastic Generation

Engineering analysis reveals that brittle plastics can generate 5 to 10 times more microplastic particles during mechanical recycling compared to ductile polymers. Product design features can exacerbate the problem. Deep ribs, sharp internal corners, and heavily textured surfaces can trap contaminants, requiring more aggressive, high-pressure washing cycles that abrade the plastic surface and release even more microplastics. Solutions involve specifying more ductile polymers, designing products with smooth, easily-cleaned surfaces, and avoiding elements like full-body shrink sleeves that delaminate into tiny fragments during processing.

As designers, our responsibility extends to anticipating these process-related impacts. The choice of plastic grade, the design of surface finishes, and the elimination of features that trap dirt are all levers we can pull to minimize microplastic generation. This requires a deeper conversation with material suppliers and recyclers to understand the real-world behavior of our designs “in the grinder.”

| Plastic Type | Shredding Behavior | Microplastic Risk | Design Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ductile (HDPE, LDPE) | Tears and stretches | Low | Preferred for recyclability |

| Brittle (PS, brittle PP) | Shatters into fragments | High | Avoid or reinforce |

| Surface-printed | Ink delamination | Medium | Use molded-in color |

| Multi-layer laminates | Layer separation | Very High | Design for mono-material |

The Design Mistake That Alienates Customers and Invites Regulation

Eco-design is not just about materials and energy; it’s about respecting the user. A design that actively prevents repair, limits functionality through software, or locks the user into a proprietary ecosystem is not only unsustainable but also anti-consumer. This practice, often termed “planned obsolescence,” creates frustration, erodes brand loyalty, and is increasingly attracting the attention of regulators. The “Right to Repair” movement is gaining global momentum, and design choices like using proprietary screws, gluing in batteries, or making spare parts unavailable are becoming significant business risks.

The trade-off here is between short-term revenue from repeat sales and long-term customer trust and brand reputation. A transparent, repair-friendly design philosophy builds a powerful connection with users. It empowers them, turning them from passive consumers into active partners in the product’s lifecycle. Publishing repair manuals, using standard fasteners, and designing modular architectures that allow for simple component swaps are powerful signals of respect.

This philosophy of openness and empowerment is a core tenet of sustainable design, extending even into the digital realm. As the Sustainable Web Manifesto states in the UX Design Institute’s guide:

If the Internet was a country, it would be the fourth largest polluter. Digital sustainability can help decrease technology’s negative impact through design choices that reduce energy usage and extend product lifecycles.

– Sustainable Web Manifesto, UX Design Institute Guide to Sustainable Digital Product Design

By making our products and services more transparent, efficient, and repairable, we not only reduce waste but also build a more resilient and loyal customer base. Avoiding anti-consumer practices is no longer just good ethics; it’s good business strategy.

Key Takeaways

- The most impactful eco-design decisions are made during the concept phase, where choices about assembly, materials, and strategy are defined.

- Effective eco-design is an exercise in managing trade-offs between conflicting goals like durability, recyclability, cost, and performance.

- Anticipating downstream consequences—from microplastic generation in recycling to customer frustration over repairability—is a critical design responsibility.

Virgin vs Secondary Materials: How to Overcome Quality Inconsistencies in Production?

The decision to use secondary (recycled) materials is fundamental to closing the loop in a circular economy. It reduces the demand for virgin resource extraction, lowers the carbon footprint of material production, and creates value from waste. However, for a designer or engineer focused on quality and consistency, recycled feedstocks present a significant challenge. Unlike virgin resins, which have predictable properties, recycled materials can exhibit variations in color, melt flow, and structural integrity from batch to batch. This is the final, practical trade-off: perfect consistency versus circularity.

Trying to force a recycled material to behave and look exactly like its virgin counterpart is often a losing battle. A more successful strategy is to design for the material’s inherent nature. This means embracing, rather than hiding, the slight variations that come with recycled content. A product can be designed to celebrate these imperfections, turning the unique “fingerprint” of the recycled material into a visible and desirable feature that tells a story of sustainability.

Case Study: The Strategic Blending Approach

Many companies successfully implementing recycled materials use a strategic blending approach. An analysis of best practices shows that blending ratios, often in the range of 30-70% recycled content with virgin material, can maintain critical performance and aesthetic standards while still achieving significant environmental benefits. The key is to design products that celebrate rather than hide these material variations. This approach turns the recycled content’s unique character into a premium sustainability feature, creating a compelling narrative that resonates with environmentally conscious consumers and justifies a potential price premium.

Overcoming quality inconsistencies also requires closer collaboration across the value chain. Designers must work with material scientists to understand the performance envelope of available recycled feedstocks and with manufacturers to adjust processing parameters. It may involve designing products with slightly thicker walls to compensate for potential lower strength or choosing color palettes that are less sensitive to minor shifts in hue. This is the frontline of practical eco-design, where creative problem-solving and technical expertise come together to make circularity a reality.

By moving beyond a simplistic checklist and embracing the complexity of these strategic trade-offs, you can elevate your practice from simply designing products to architecting a more sustainable future. Start today by questioning one assumption in your current project and exploring a more circular alternative.