The greatest financial risk in land management isn’t visible degradation; it’s the failure to identify systemic ecological breakdowns just before the point of no return.

- Beyond visual cues, true assessment requires analyzing “silent killers” like soil compaction and disruptions in hydrological cycles.

- Prioritizing interventions based on leverage points, such as upstream riparian zones and natural regeneration, yields far greater ROI than broad, unfocused efforts.

Recommendation: Shift from a reactive, symptom-based assessment to a proactive, risk-based valuation of natural capital to secure long-term asset value and avoid irreversible losses.

For land conservationists and investors in natural capital, a landscape can present a deceptive picture. What appears to be a stable, albeit low-productivity, asset might be an ecosystem on the brink of irreversible collapse. The common approach to assessment—looking for obvious signs of erosion or barren patches—is dangerously insufficient. It is a reactive posture that identifies problems only after the most cost-effective solutions are off the table. This method completely misses the subtle, systemic failures accumulating beneath the surface.

The conversation around restoration often gravitates towards simplistic solutions like mass tree planting or basic erosion control. While these have their place, they fail to address the root causes of degradation. The real challenge lies in diagnosing the health of the underlying ecological engine. Is the soil’s structure compromised? Are nutrient cycles broken? Is the land losing its ability to retain water? These are the questions that determine an ecosystem’s trajectory and, consequently, its long-term value as an asset.

This is where a paradigm shift is imperative. The key isn’t merely to spot what’s already broken, but to identify the tipping points before they are crossed. It’s about understanding the closing restoration window—the critical, time-sensitive period where intervention is still viable and financially sensible. This guide abandons surface-level diagnostics to provide a framework for identifying these deep-seated vulnerabilities. We will explore how to detect these silent killers, prioritize interventions for maximum impact, and ultimately translate ecological health into a tangible metric on your balance sheet.

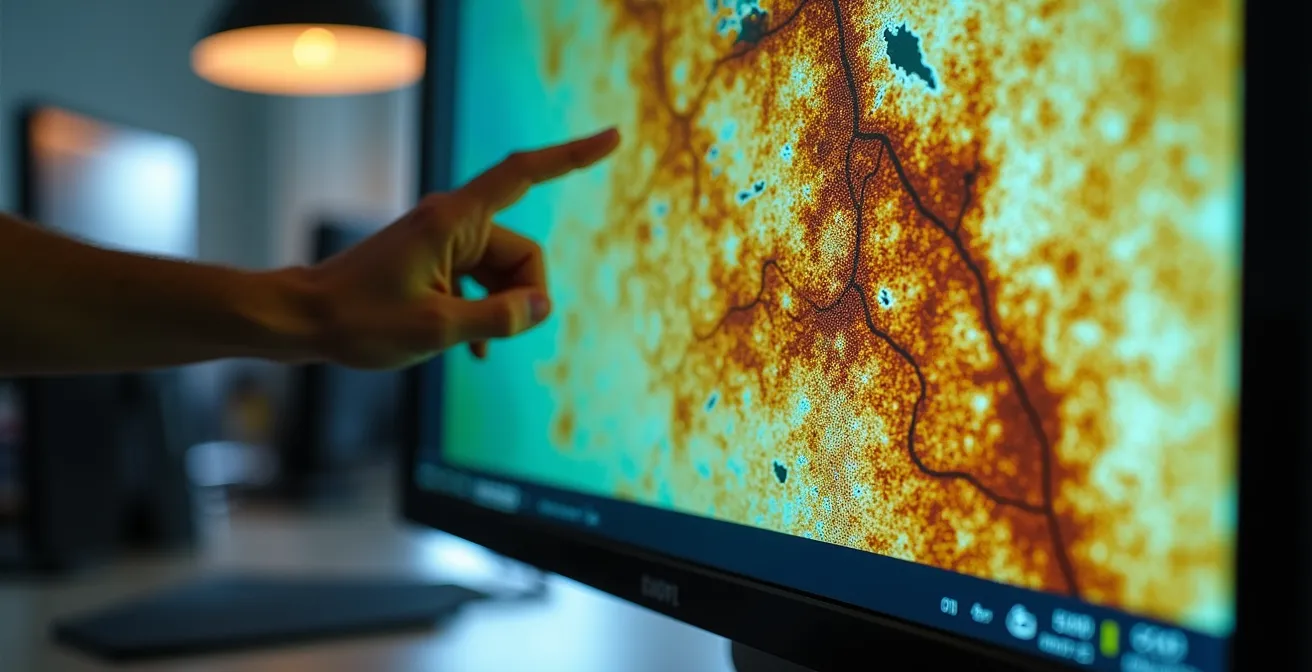

For those who prefer a visual summary, the following video offers a compelling overview of on-the-ground ecosystem restoration actions and their importance, complementing the strategic framework detailed in this guide.

To effectively navigate this complex evaluation, this article is structured to move from foundational diagnostics to high-level financial strategy. The following sections will provide a clear path for assessing and acting upon the true state of your natural assets.

Summary: A Strategic Framework for Assessing Degraded Ecosystems

- Why Is Soil Compaction the Silent Killer of Agricultural Productivity?

- How to Use Satellite Imagery to Map Vegetation Loss over 5 Years?

- Natural Regeneration vs Tree Planting: Which Recovers Biodiversity Faster?

- The Financial Error of Delaying Erosion Control on Sloped Land

- In Which Order Should You Restore Riparian Zones to Maximize Water Quality?

- Why Is a Wetland Worth More Than a Parking Lot in Flood Prone Areas?

- How to Intervene in Local Feedback Loops to Prevent Desertification?

- How to Account for Natural Capital on Your Balance Sheet?

Why Is Soil Compaction the Silent Killer of Agricultural Productivity?

Before any visible sign of degradation, like erosion or vegetation die-off, a critical systemic failure often occurs unnoticed: soil compaction. This is not merely “hard ground”; it’s the collapse of the soil’s essential architecture. Heavy machinery, improper tillage, or overgrazing squeezes the life out of the soil, eliminating the macropores that act as its lungs and circulatory system. The immediate consequence is a catastrophic loss of function. According to research from Penn State Extension, soil compaction causes a decrease in macropores, resulting in much lower water infiltration rates and severely reduced hydraulic conductivity. Water that should be absorbed runs off, taking topsoil with it and starving plant roots of both moisture and oxygen.

This silent killer directly sabotages productivity and resilience. A compacted field requires more irrigation to achieve the same results, increases flood risk, and becomes inhospitable to the microbial life essential for nutrient cycling. Ignoring compaction is a fundamental error in land assessment. It means you are evaluating the land based on its current, compromised state, not its latent potential. The restoration window for compaction is open early on but narrows rapidly as topsoil loss accelerates.

Fortunately, nature offers potent, low-cost solutions if deployed in time. In humid agricultural regions, biological agents can be powerful allies. As noted in a study on soil structure, in areas with simplified tillage systems, earthworms can help alleviate structure degradation by re-establishing pore networks. Encouraging this type of natural recovery is a primary, cost-effective intervention that must be considered before expensive mechanical solutions become the only option. The presence or absence of a healthy earthworm population can be a more telling indicator of soil health than a surface-level visual inspection.

How to Use Satellite Imagery to Map Vegetation Loss over 5 Years?

While on-the-ground indicators are vital, a landscape-scale view is essential for tracking degradation over time. Satellite imagery, specifically using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), provides an invaluable tool for this analysis. However, using it effectively requires moving beyond a simple “green is good, brown is bad” interpretation. The real power of NDVI lies in its ability to detect vegetation under stress long before it dies. It measures the contrast between near-infrared light (which vegetation reflects) and red light (which it absorbs), providing a quantitative measure of plant health.

A static NDVI map shows a snapshot in time. The strategic approach is to analyze a time-series over at least five years to identify trends. Is an area consistently showing lower NDVI values during peak growing seasons compared to previous years? Are the boundaries of low-NDVI zones expanding? This temporal analysis reveals the velocity of degradation. The Alabama Cooperative Extension System reports that NDVI values between 0.2 to 0.5 indicate moderate stress, while values below 0.4 signal critical stress. Identifying a property that is trending downwards from 0.5 towards 0.4 over several seasons is a major red flag; the ecosystem’s resilience is actively eroding.

This data-driven approach allows for targeted intervention. Instead of treating an entire property uniformly, you can focus resources on the specific zones showing the earliest and most rapid decline. This is the essence of intervention triage: applying effort where the risk of crossing a tipping point is highest. This method transforms satellite data from a passive monitoring tool into an active, strategic guide for deploying capital and conservation efforts before the landscape enters a state of critical failure.

Natural Regeneration vs Tree Planting: Which Recovers Biodiversity Faster?

When faced with a degraded, deforested area, the instinctive response is often to initiate a mass tree-planting campaign. This approach is visible, easy to fund, and provides a sense of immediate action. However, it is frequently not the most effective or efficient strategy for ecological recovery. Natural regeneration—the process of allowing and assisting an ecosystem to recover on its own—often outperforms active planting, particularly in terms of biodiversity and cost-effectiveness. This is not a passive “do nothing” approach; it involves removing pressures like grazing, controlling invasive species, and enriching the soil to create conditions where native seed banks can thrive.

The financial and ecological arguments are compelling. One study shows a 56 percent higher rate of biodiversity in natural regeneration projects compared to manual tree-planting. This is because natural succession allows a complex, resilient, and locally-adapted mosaic of species to establish, rather than a monoculture of planted saplings. From a cost perspective, the choice is also nuanced. A 2024 *Nature Climate Change* study found that across 138 low- and middle-income countries, natural regeneration has lower abatement costs across approximately 46% of the land suitable for reforestation.

The decision is not always one or the other. A hybrid approach is often the most strategic, using targeted planting to create “islands of fertility” that accelerate natural succession across the wider landscape. As one expert puts it:

A mix of planted and naturally regenerated forests is often the best way to balance society’s many demands on forests.

– Jeffrey R. Vincent, Duke University, Nature Climate Change

For an investor or conservationist, the takeaway is critical: do not default to tree planting. Evaluate the site’s potential for natural recovery first. If a native seed bank exists and pressures can be removed, assisting natural regeneration is likely the superior strategy for building a robust, biodiverse, and resilient ecosystem asset.

The Financial Error of Delaying Erosion Control on Sloped Land

On sloped terrain, soil is not a static asset; it is in a constant state of flux, held in place by vegetation. Delaying erosion control on these lands is a compounding financial error. Each rainfall event that carries away topsoil is not just a loss of sediment; it is a permanent depreciation of the land’s core productive asset. The soil that is lost contains the highest concentration of organic matter and nutrients, and its departure initiates a vicious feedback loop: less fertile soil supports less vegetation, which in turn leads to more erosion. This downward spiral rapidly diminishes the land’s capacity for carbon sequestration, water retention, and agricultural productivity.

The scale of the missed opportunity is immense. Global research published in *Nature* reveals that 215 million hectares has the potential for natural forest regeneration across tropical countries, representing a massive carbon sequestration potential. Sloped lands are a key part of this equation. Allowing them to degrade is akin to writing off a high-yield asset. The cost of intervention increases exponentially with time. What might initially be solved with low-cost vegetative barriers or cover crops can quickly escalate to requiring expensive and invasive engineering solutions like terracing or retaining walls once deep gullies form.

The urgency is therefore financial. Proactive, low-cost measures are not expenses; they are investments that protect the principal value of the land asset. Taking immediate action to stabilize soil is one of the highest-return activities in land management. It halts capital depreciation and preserves the future restoration and revenue-generating potential of the property, whether through agriculture, carbon credits, or ecotourism.

Action Plan: Implementing Cost-Effective Erosion Prevention

- Boost Organic Matter: Systematically return crop residue to the soil after harvest to improve its structure and water-holding capacity.

- Deploy Cover Crops: Plant cover crops like clover or vetch during the off-season to shield the soil surface from rain and wind.

- Utilize Soil Amendments: Apply compost and manure to build healthy soil aggregates that are more resistant to erosion.

- Minimize Tillage: Adopt no-till or reduced-tillage practices to maintain soil structure and prevent the breakup of protective aggregates.

- Maximize Surface Residue: Leave as much crop residue as possible on the soil surface to act as a natural armor against erosive forces.

In Which Order Should You Restore Riparian Zones to Maximize Water Quality?

Riparian zones—the strips of land alongside rivers and streams—are the arteries of a landscape. Their health is directly linked to the health of the entire watershed. When these zones are degraded, they cease to function as natural filters, leading to polluted waterways, increased erosion, and loss of critical habitat. For investors and conservationists, restoring these zones presents a high-leverage opportunity, but the order of operations is paramount. Randomly restoring patches along a river is inefficient; a strategic, sequential approach is required to maximize the return on investment in terms of water quality.

The non-negotiable principle is to start upstream. Restoring the headwaters and upper reaches of a stream first creates a cascade of positive effects downstream. A healthy upstream riparian buffer filters sediment and pollutants at the source, preventing them from contaminating the entire watercourse. It stabilizes stream banks, reducing the erosion that would otherwise undermine downstream restoration efforts. Attempting to restore a downstream section while the headwaters are still actively eroding is like mopping the floor while the sink overflows—a futile and costly endeavor.

The UN’s approach to ecosystem restoration emphasizes tackling threats at their source. For freshwater ecosystems, this means addressing pollution and infrastructure impacts methodically. This logic applies directly to riparian sequencing. The first step is to stabilize the most vulnerable upstream areas with native vegetation and bioengineering techniques (like log weirs). Once these are established and begin to function, efforts can progressively move downstream. This sequence ensures that each restored section is protected by the healthy, functioning zone above it, creating a resilient and self-sustaining system. This “upstream-first” triage strategy ensures that every dollar invested contributes to a cumulative and lasting improvement in the entire aquatic ecosystem.

Why Is a Wetland Worth More Than a Parking Lot in Flood Prone Areas?

In conventional real estate development, converting a wetland into a parking lot or commercial space is often seen as “creating value.” This perspective is dangerously shortsighted, especially in areas prone to flooding. It confuses a single-purpose revenue stream with a multi-faceted, high-value asset. A wetland is a piece of natural infrastructure that provides a suite of valuable ecosystem services for free—services that are incredibly expensive to replicate with man-made “grey” infrastructure. Its primary function in a flood-prone area is stormwater management and flood control. A wetland acts as a natural sponge, absorbing and slowly releasing massive volumes of water, reducing peak flood levels and protecting downstream properties.

The financial case becomes undeniable when you factor in the full scope of benefits and liabilities. As UN Environment Programme data shows, peatlands cover only 3 per cent of the world’s land but store almost one-third of all the carbon in its soil. Draining a wetland not only destroys a critical flood defense but also releases a significant carbon bomb and eliminates a vital biodiversity habitat. A parking lot, by contrast, generates a single revenue stream while creating a new liability: it increases stormwater runoff, requires costly maintenance and resurfacing, and contributes to the urban heat island effect.

The following table, based on principles from the UN Decade on Restoration, starkly illustrates the value gap between these two asset types. When a holistic, long-term view is taken, the wetland is not just an environmental amenity; it is a superior financial asset.

| Asset Type | Primary Function | Additional Benefits | Maintenance Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wetland | Flood control | Water filtration, carbon sequestration, biodiversity habitat, recreation | Low |

| Parking Lot | Vehicle storage | Single revenue stream | High (resurfacing, drainage) |

| Concrete Retention Basin | Stormwater management | Limited additional benefits | High (dredging, repairs) |

For an investor, protecting or restoring a wetland in a developing, flood-prone area is a shrewd strategic move. It represents a low-maintenance, high-value asset that mitigates regional risk and offers multiple, stackable co-benefits, from carbon credits to enhanced property values for surrounding protected lands.

Key takeaways

- Degradation is a process, not an event; identify systemic failures like compaction and broken feedback loops before they become irreversible.

- Prioritize interventions based on ecological leverage, such as upstream restoration and natural regeneration, to maximize financial and ecological returns.

- Natural capital is a tangible asset; its depreciation through degradation must be accounted for on the balance sheet to reflect true financial risk.

How to Intervene in Local Feedback Loops to Prevent Desertification?

Desertification is the ultimate expression of a negative feedback loop. It begins with the loss of vegetation cover, which exposes soil to sun and wind. This leads to increased evaporation and soil erosion. The degraded soil can no longer support plant life, leading to further vegetation loss, and the cycle accelerates. An ecosystem caught in this spiral will not self-correct; without intervention, it will continue its trajectory towards a barren, unproductive state. The key to preventing this catastrophic outcome is to intervene early and disrupt the feedback loop at a micro-scale.

The mistake is to attempt large-scale, dramatic interventions like planting a forest in a highly degraded area. This is doomed to fail because the underlying conditions—poor soil, lack of water retention, and high evaporation—cannot support mature trees. The strategic approach is to focus on creating small but resilient “islands of fertility.” These are localized patches where the negative feedback loop is intentionally broken and replaced with a positive one. By focusing resources and effort on small, manageable plots, a new dynamic can be initiated.

This process begins with stabilizing the ground and reintroducing life. Techniques like building small check dams or digging Zai pits trap water and organic matter, creating a concentrated zone of moisture and nutrients. Introducing hardy pioneer species and organic compost kick-starts microbial activity and nutrient cycling. As these islands of fertility become established, they begin to positively influence their immediate surroundings. They trap wind-blown seeds, provide shade, and slowly improve soil conditions in an expanding radius. This gradual, patient approach is the only effective way to reverse the momentum of desertification and initiate a self-sustaining recovery process.

Your Field Guide: Micro-Interventions to Reverse Desertification

- Stabilize and Slow: First, stabilize the ground and reduce surface runoff using small-scale physical barriers or contour swales.

- Reintroduce Organic Matter: Add compost and introduce fast-growing, early-successional plants to begin rebuilding topsoil.

- Encourage Pioneer Species: Foster the colonization by fungi, bacteria, and nitrogen-fixing plants that prepare the soil for more complex vegetation.

- Create “Islands of Fertility”: Concentrate water and nutrients in specific locations using techniques like Zai Pits to create resilient starting points for recovery.

- Be Patient and Gradual: Begin the restoration process slowly. Do not attempt to plant forests immediately; focus on building the foundational soil health first.

How to Account for Natural Capital on Your Balance Sheet?

For too long, the value of nature has been external to economic calculation. For investors in natural capital, this must change. Treating ecological assets and liabilities as mere footnotes is a critical accounting failure that conceals immense risk and opportunity. To make informed decisions, natural capital must be brought onto the balance sheet. This means moving beyond traditional accounting to quantify the value of ecosystem services and the financial risk of their degradation.

This is not a purely academic exercise; it has tangible financial implications. According to UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration estimates, the restoration of 350 million hectares of degraded ecosystems could generate US$9 trillion in ecosystem services between now and 2030. These services—water filtration, pollination, flood control, carbon sequestration—are real economic benefits. A healthy forest isn’t just standing timber; it’s a carbon-capturing, water-purifying, and biodiversity-hosting asset. Conversely, soil erosion is not an environmental issue; it is a natural capital liability, a quantifiable “value at risk” that depreciates the worth of your landholding.

Integrating this into a balance sheet requires a new framework. The table below provides a simplified template for how to begin conceptualizing this. Traditional physical assets are listed alongside their natural capital counterparts. Crucially, it also includes a column for natural capital liabilities—the potential costs associated with ecological degradation. By assigning even conservative values to these items, a far more accurate picture of a property’s true worth and risk exposure emerges. This approach transforms land management from a cost center into a strategic asset management discipline.

| Traditional Assets | Natural Capital Assets | Natural Capital Liabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Physical infrastructure | Timber & Carbon Value of Forest | Soil Erosion Risk (Value at Risk) |

| Financial investments | Water Filtration Value of Wetland | Pollution Cleanup Provision |

| Inventory | Biodiversity Credits Potential | Degradation Remediation Costs |

| Equipment | Ecotourism Revenue Stream | Climate Risk Exposure |

Ultimately, a proactive and evaluative approach is not just best practice—it is the only rational strategy. By shifting your assessment from visible symptoms to underlying systemic health and integrating natural capital into your financial framework, you transform risk into opportunity and secure the long-term value of your land assets. Begin implementing this risk-based approach today to ensure your portfolio is resilient, productive, and truly sustainable.