Humanity and the environment

The relationship between humanity and the environment has never been more critical to understand. As the dominant species on Earth, humans have transformed landscapes, altered atmospheric composition, and reshaped ecosystems on an unprecedented scale. Yet this same capacity for change holds the key to creating a more sustainable future. Understanding how our daily choices, economic systems, and societal structures interact with natural processes is the first step toward meaningful action.

This comprehensive exploration examines the multifaceted connections between human activity and environmental health. From the carbon footprint of our consumption patterns to the inspiring examples of communities living in greater harmony with nature, we’ll uncover both the challenges we face and the opportunities we have to forge a more balanced relationship with our planet. Whether you’re just beginning to explore environmental issues or seeking to deepen your understanding, this resource will equip you with the knowledge to make informed decisions.

Our Environmental Footprint: Understanding Human Impact

Every human action, from the food we eat to the energy we consume, leaves an imprint on the natural world. This environmental footprint represents the cumulative effect of our resource use, waste generation, and ecosystem alteration. Recognizing the scale and nature of this impact is essential for developing effective responses.

Resource Consumption and Depletion

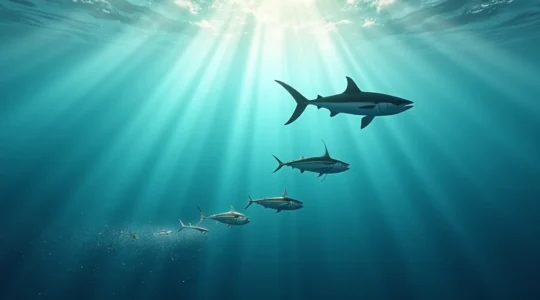

Humanity currently uses natural resources at a rate that exceeds Earth’s regenerative capacity. Studies indicate that we would need approximately 1.7 Earths to sustainably support current consumption levels. This overexploitation manifests in deforestation, overfishing, groundwater depletion, and soil degradation. Forests that took centuries to grow disappear in decades, while fish populations collapse under industrial harvesting pressure.

The concept of ecological debt describes this deficit—we’re borrowing from future generations by depleting resources faster than they can replenish. Fossil fuels, formed over millions of years, are extracted and burned within mere generations, creating a one-way flow that cannot continue indefinitely.

Pollution Across All Spheres

Human activity introduces contaminants into air, water, and soil systems worldwide. Air pollution from industrial processes, transportation, and energy production affects billions of people, particularly in rapidly developing urban areas. Waterways carry agricultural runoff, industrial waste, and plastic debris, with an estimated 8 million tons of plastic entering oceans annually.

These pollutants don’t respect boundaries—they circulate through atmospheric currents, ocean streams, and food webs, eventually reaching even the most remote locations. Microplastics have been discovered in Arctic ice, deep ocean trenches, and human bloodstreams, illustrating the pervasive nature of modern contamination.

Habitat Destruction and Fragmentation

As human populations expand and economies develop, natural habitats shrink and fragment. Agriculture alone occupies roughly half of Earth’s habitable land, transforming diverse ecosystems into monoculture fields. Urban sprawl, infrastructure development, and resource extraction further reduce wild spaces, creating isolated habitat patches where once-continuous ecosystems thrived.

This fragmentation disrupts wildlife migration patterns, limits genetic diversity, and makes species more vulnerable to local extinction. The consequences ripple through entire food webs, as the loss of one species affects countless others in interconnected relationships.

Climate Change and Human Activity

Perhaps no environmental challenge illustrates the human-environment relationship more clearly than climate change. The burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial agriculture have increased atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations by over 50% since pre-industrial times, driving global temperature increases and cascading environmental effects.

The evidence is unequivocal: rising global temperatures, melting ice caps, shifting precipitation patterns, and increasing extreme weather events all point to a climate system responding to human influence. Coastal communities face rising sea levels, agricultural regions experience altered growing seasons, and ecosystems struggle to adapt to rapid change. The feedback loops within the climate system mean that some changes may accelerate—melting permafrost releases additional greenhouse gases, while reduced ice cover decreases Earth’s reflectivity, leading to further warming.

Understanding the greenhouse effect helps clarify this connection. Certain gases trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere much like glass in a greenhouse. While this natural process makes our planet habitable, the rapid increase in these gases—primarily from burning coal, oil, and natural gas—intensifies the effect beyond historical norms. The result is a warming planet with profound implications for weather patterns, ocean chemistry, and ecosystem stability.

Sustainable Living: Pathways Toward Harmony

Despite these challenges, humanity possesses remarkable capacity for innovation and adaptation. Sustainable living practices demonstrate that human needs can be met while respecting ecological limits. These approaches recognize that human wellbeing ultimately depends on environmental health.

Circular Economy and Waste Reduction

The traditional linear economy—extract, produce, consume, dispose—is giving way to circular models that minimize waste and maximize resource efficiency. In circular systems, products are designed for durability, repairability, and eventual recycling or composting. Materials flow in closed loops rather than ending in landfills or incinerators.

Practical applications range from industrial symbiosis, where one company’s waste becomes another’s raw material, to consumer choices like buying secondhand goods, composting organic waste, and choosing products with minimal packaging. Some communities have achieved waste diversion rates exceeding 70% through comprehensive recycling, composting, and reuse programs.

Renewable Energy Transition

Shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources represents one of the most significant opportunities to reduce environmental impact. Solar, wind, hydroelectric, and geothermal technologies have matured rapidly, with costs declining dramatically. In many regions, renewable electricity is now cheaper than fossil fuel alternatives, making the transition economically attractive as well as environmentally necessary.

This energy transformation extends beyond electricity generation to transportation, heating, and industrial processes. Electric vehicles, heat pumps, and green hydrogen demonstrate how renewable energy can power diverse applications. The decentralization of energy production—through rooftop solar panels and local wind installations—also increases resilience and energy independence.

Sustainable Food Systems

Agriculture connects human sustenance directly to environmental impact. Current industrial farming practices contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, and biodiversity loss. However, alternative approaches demonstrate that food production can work with natural systems rather than against them.

Regenerative agriculture improves soil health, sequesters carbon, and supports biodiversity while producing nutritious food. Techniques include crop rotation, cover cropping, reduced tillage, and integrated livestock management. Urban agriculture, local food systems, and plant-forward diets also reduce the environmental footprint of feeding humanity. Shifting dietary patterns toward more plant-based foods can substantially decrease land use, water consumption, and emissions associated with food production.

Conservation and Biodiversity Protection

Protecting Earth’s remaining wild spaces and the species they harbor is fundamental to environmental health. Biodiversity—the variety of life at genetic, species, and ecosystem levels—provides essential services that humans depend upon: pollination, water purification, climate regulation, and nutrient cycling, among countless others.

Conservation efforts take multiple forms. Protected areas like national parks, marine reserves, and wildlife corridors preserve critical habitats and allow ecosystems to function with minimal human interference. Currently, approximately 15% of land and 7% of oceans enjoy some form of protection, though conservation biologists recommend significantly higher percentages to adequately safeguard biodiversity.

Beyond protected areas, conservation increasingly focuses on landscape-scale approaches that integrate human activities with ecological needs. Wildlife corridors connect habitat fragments, allowing species movement and genetic exchange. Sustainable forestry and fishing practices attempt to balance resource extraction with ecosystem health. Community-based conservation recognizes that local populations often have both traditional knowledge and vested interests in protecting their environments.

The restoration of degraded ecosystems offers hope for reversing some environmental damage. Reforestation projects, wetland restoration, and coral reef rehabilitation demonstrate that natural systems possess remarkable regenerative capacity when given the opportunity. These efforts not only support biodiversity but also provide employment, improve local climate resilience, and enhance human wellbeing.

The Role of Education and Collective Action

Knowledge empowers action. Environmental education helps people understand the consequences of their choices and the possibilities for positive change. When individuals grasp the connections between personal behavior and global environmental health, they’re better equipped to make informed decisions—from daily consumer choices to civic engagement and career paths.

Effective environmental education goes beyond presenting problems; it cultivates systems thinking and solution-oriented mindsets. Understanding how energy, food, water, and material systems interconnect reveals leverage points for intervention. Recognizing that environmental challenges are also social, economic, and political issues encourages holistic approaches.

Collective action amplifies individual efforts. Communities organizing for cleaner air, citizens advocating for environmental policies, and movements demanding corporate accountability demonstrate that coordinated action can drive systemic change. The transition toward sustainability requires not just individual behavioral changes but also transformations in infrastructure, economic incentives, and governance structures—changes that emerge from organized collective will.

The relationship between humanity and the environment is not predetermined. Our species has demonstrated both destructive and regenerative capacities. By understanding our impact, embracing sustainable practices, protecting biodiversity, and working collectively, we can shift toward a future where human societies thrive within planetary boundaries. The challenge is substantial, but so too is our capacity for innovation, adaptation, and care for the living world that sustains us.

Why Top Predators Carry a Toxin Load 10x Higher Than Their Prey

The game you hunt or fish you catch isn’t just food; it’s a cumulative record of environmental toxins, and understanding its story is key to protecting your health. Fat-soluble toxins like PCBs are stored in an animal’s blubber and tissue,…

Read more

How Microplastics Enter the Human Bloodstream Through Common Food Sources

The pervasive threat of microplastics extends far beyond ocean pollution and landfills. The most significant risk of human contamination originates from invisible fragmentation pathways within our own homes. Everyday activities, such as doing laundry and drinking bottled water, systematically break…

Read more

How Synthetic Fertilizers Contaminate Drinking Water Sources via Nitrate Runoff?

The contamination of our drinking water by synthetic fertilizers is not an accident; it is a predictable biochemical cascade of systemic failures with devastating public health consequences. Excess nitrogen from fertilizers inevitably leaches into groundwater as nitrate, a compound linked…

Read more

Why Large-Scale Monocultures Are More Susceptible to Rapid Disease Spread?

The perceived efficiency of large-scale monoculture masks a profound systemic fragility, concentrating biological and financial risk to an unsustainable degree. Monoculture systems create a uniform landscape where disease can spread without resistance, leading to catastrophic yield loss. Diversified agroecological models…

Read more

The Hidden Flood Risk: Why Your Suburban Dream Home Is a Ticking Time Bomb

The perceived safety and tranquility of the suburbs is a dangerous illusion when it comes to flooding. Low-density sprawl, characterized by vast, non-absorbent surfaces like roads and driveways, dangerously amplifies rainwater runoff, turning moderate storms into destructive flash floods. The…

Read more